As you may know, I am one of the writing team on Frances Wilson's ArtMuseLondon website, where this article first appeared. For a handsome range of reviews and thought pieces covering all genres of art and music, please pay the site a visit here.

Wednesday, 16 December 2020

Pigment of the imagination: Brian and Roger Eno, 'Mixing Colours (Expanded)'

Sunday, 29 November 2020

Spired and emotional: the Oxford Lieder Festival 2020

As you may know, I am one of the writing team on Frances Wilson's ArtMuseLondon website, where this article first appeared. For a handsome range of reviews and thought pieces covering all genres of art and music, please pay the site a visit here.

Monday, 16 November 2020

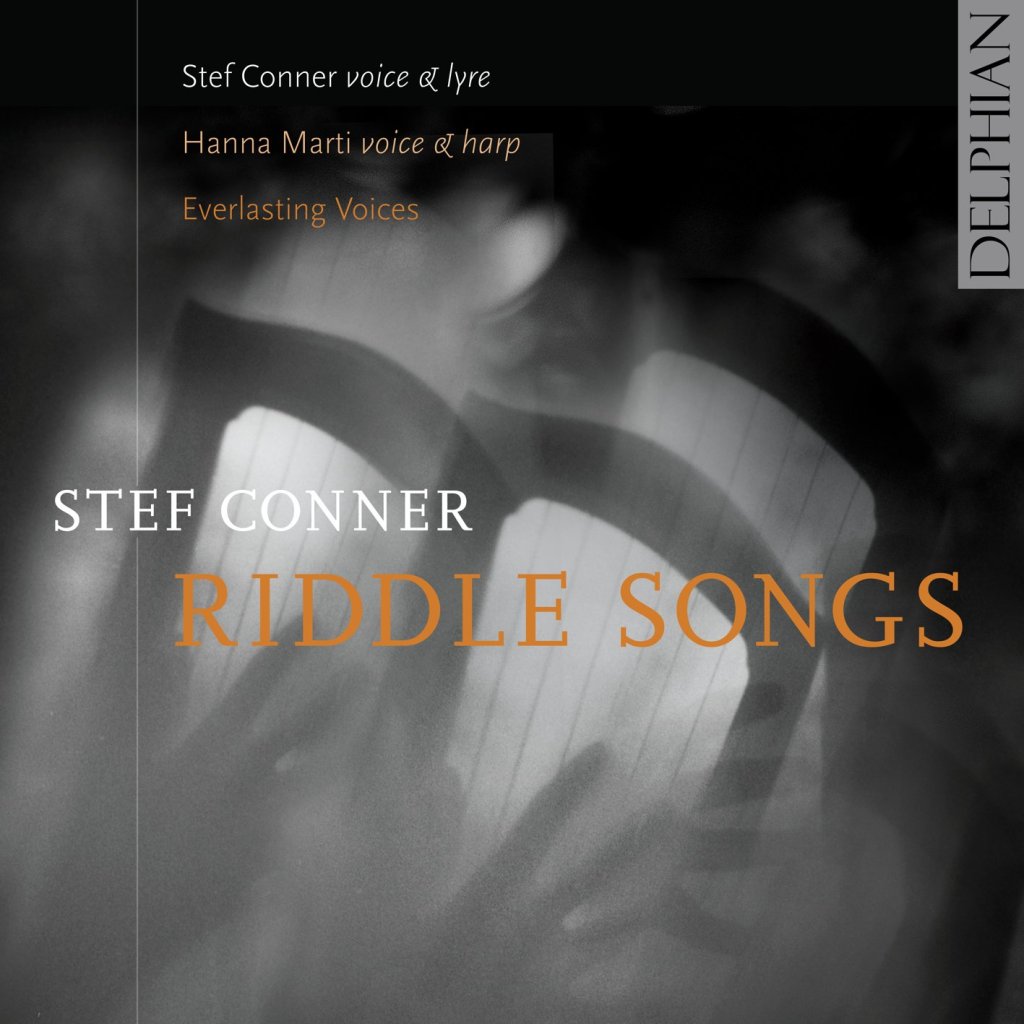

Mystery lays: Stef Conner, 'Riddle Songs'

As you may know, I am one of the writing team on Frances Wilson's ArtMuseLondon website, where this article first appeared. For a handsome range of reviews and thought pieces covering all genres of art and music, please pay the site a visit here.

*

This startling, life-affirming record somehow manages a feat that has otherwise eluded science so far: time travel. Stef Conner has composed a suite of songs that demonstrate how, through the arts, the past is all there, all at once, running parallel to our present. What are its secrets?

A bit of background (although Conner’s liner notes for the CD are so informative and engrossing, I don’t want to simply replicate extracts here). Conner takes particular interest in combining research with composition: the theme of this album rests on the intriguing fact that there are no surviving Old English songs. Or, to be more precise, we have poetry and text, but no extant musical instruction or notation to go with them. Conner sets out to bring the words to life with new settings. Among these are a group of riddles, which give the album its name, as well as an overarching metaphor for the central puzzle behind the verse: that we can never know exactly how the music would have sounded.

From the first glance at the evocative cover image, the disc looks set to catapult the listener back to an era when even ‘early music’ was in the future. Conner (alto voice, lyre) collaborates with Hanna Marti (soprano voice, harp) and Everlasting Voices, a ‘super-group’ of singers who assemble for specific projects, here conducted by Jonathan Brigg. Marti contributes or co-writes three tracks. The arrangements honour authentic instrumentation and tunings, without forcing anything material from the present day into the album’s soundworld.

However, this is not so much historically-informed, as historically inspired performance – and we are not listening to a reconstruction, some kind of attempt at reanimating a lost artform. This is brand new writing, brand new music – and it sounds like it. Conner is quick to flag where she references known early motifs and these can range from taking harmonic inspiration for a mnemonic rhyme from medieval Latin recitation settings (the splintered ‘Rune Poem’) to incorporating drones to simulate bagpipes (‘Song-pack’). But while at pains to acknowledge these launchpad characteristics, Conner is not reliant on them: instead, they are springboard for her own compositional verve and flair.

Less than two minutes into the album and second track ‘Fire’ makes it clear that this is something different: the unexpected full force of Everlasting Voices bending chords around a winding tenor solo, the heat-intensity audible. The arrangement then tracks the demands of the lyric (the Phoenix myth), calming and resolving before building again to agitated repetition as flame engulfs the bird, then into the ambiguous closing hint at resurrection. Mirror track ‘Ice’, near the record’s close, uses a similar pattern of tension and release (no spoilers, but listen out for the modest jump-scare!) on an even more epic scale, the group nudging the storytelling along with dissonance/harmony as the narrative dictates.

But even these arrangements are spare and steady, and much of the album is sparser still. It feels as though Conner has constructed a set of elements or patterns and made the most of the combinations they provide. Vocally, there is Everlasting Voices and the mix of sounds they provide; but Conner has also decided to sing both solo, and in duet with Marti. There are accompaniments by solo lyre, solo harp, sometimes both are together, other times both are absent. As a result, very few tracks present themselves with exactly the same mix of voices and instruments so, accordingly, there is always some variation in mood. There is no sense of chant or litany to fix this music in a tradition: its modern sensibility always wins through.

There are exceptions, of course, to prove this rule. The ‘Rune Poem’ I mentioned above is split into segments that provide a consistent, anchoring thread throughout the disc, and is sung in its five-part entirety by Conner and Marti. Their voices complement each other beautifully and blend naturally: following the same melodic pattern (with the different colours/timbres from their own registers) they almost sound like a multi-tracked entity. Two tracks, ‘Flint’ and ‘Night-bard’, feature Conner accompanying herself alone on lyre, and the added intimacy this provides make one hope – without diminishing the shared achievement of this project in any way – that a solo record may lie in the future.

(Video by Foxbrush Films)

The album overall is utterly unafraid of space (plaudits to Paul Baxter here, too, for such three-dimensional clarity in the production). Key pauses are embraced. Even the lack of sustain from the lyre is used ingeniously, offsetting any sense of ethereal fragility with its blunt pulse – try ‘Seed Spell’ to hear how the voices are suspended above the percussive strum, almost like an acoustic click-track supporting the song’s ritualistic nature. Elsewhere, on ‘Tide-mother’, Marti’s cascading, rippling harp figure recalls the suggested answer to the text’s riddle, water.

If setting a text to an onomatopoeic accompaniment calls to mind lieder or mélodies, no bad thing. I found this album spoke most clearly to me as art song, with its placing of existing verse in sympathetic settings that allow the instruments used to both serve the needs of the text while acting as the voice’s equal. And ‘Riddle Songs’ makes an excellent song cycle, with its multiple underlying themes (mythology, nature and the elements) and carefully-plotted sequencing that both builds to a climax and brings the album full circle.

The record company calls this a ‘concept album’, and Conner herself has described it as ‘prog-choral’. In both cases, this is a little like saying “we have created this CD especially for you, Adrian”: however, the descriptions are just, as this record can cross genres quite comfortably. Anyone who follows, say, Dead Can Dance, cherishes the ‘Mystère des Voix Bulgares’ albums, or keeps an eye on the ECM New Series label (think Trio Mediaeval, especially) is sure to enjoy ‘Riddle Songs’.

It’s a delight to discover an album steeped in history and heritage that, crucially, sounds so contemporary. A stunningly well-realised work.

*

‘Riddle Songs’ is out now on Delphian Records – you can buy it directly from their online store: https://www.delphianrecords.com/products/stef-conner-riddle-songs

Sunday, 1 November 2020

Yes, surprises: Rick Simpson, 'Everything All of the Time: Kid A Revisited'

As you may know, I am one of the writing team on Frances Wilson's ArtMuseLondon website, where this article first appeared. For a handsome range of reviews and thought pieces covering all genres of art and music, please pay the site a visit here.

*

This album is an extraordinary achievement – certainly no ordinary ‘covers project’. Rick Simpson and his ensemble wilfully tackle head-on perhaps the original writers’ most elusive set of tracks and, fittingly, bring the same sense of adventure to the material as Radiohead might recognise from recording much of their music first time around.

It’s impossible to approach a record like this – a song-for-song interpretation of Radiohead’s fourth album ‘Kid A’, released in celebration of its 20th anniversary – without mentally rewinding to one’s experience of the parent LP. Hindsight, and a handsome sequence of Radiohead albums since, help to give ‘Kid A’ a clear place in the scheme of things. But it remains an impressively strange album – not necessarily in its sound (it wears its electronica / modern composition influences on its sleeve like a fluorescent armband), but more in its approach and attitude.

In fact, Radiohead had taken great strides with every record, from a slightly muddy debut album, to the scarily assured follow-up ‘The Bends’, to the expansive, precision-prog of critical and commercial smash ‘OK Computer’. This time, however, the steps leading up to the next giant leap were tense and tentative. Reading back about how the band came to create ‘Kid A’, it feels as though they had a kind of collective ‘freeze’ in their ability to function; a sort of slow-building Y2K problem personified by five blokes in a studio.

And even though the album is its own kind of masterpiece, I think its traumatic origins are audible, in its grooves. I find it amazing still that they had enough material for two albums – yet the follow-up with the leftovers, ‘Amnesiac’, has the lion’s share of unshakeable melodies. And since then, they have constantly shifted this way and that, carving out their unique niche between the anthemic and the avant-garde. Think how many Radiohead songs (whether earlier – ‘Planet Telex’, ‘Lucky’, ‘The Bends’, ‘Karma Police’ – or later – ‘Burn the Witch’, ‘Supercollider’, ‘House of Cards’, ‘You and Whose Army?’, ‘There There’), whatever sense of angst or danger they carry, still have sections, even particular moments, that take you to a point of euphoria and release. But there in the middle, ‘Kid A’ is curiously bereft of those moments. It’s taken a crack team of jazz musicians to draw them out.

Radiohead are widely covered, not least in jazz – perhaps because they have such a distinctive musical stamp, especially in Thom Yorke’s unmistakeable vocals. I can imagine artists seeing a clear way through to making a Radiohead track their own, especially as an instrumental. I’d also speculate that as many of their tracks embrace sophistication (unusual time signatures, song structures) without being over-complex or messy, they must provide appealing starting points for improvisation.

But as bandleader and arranger, Simpson has set himself the unenviable challenge of re-working an entire Radiohead album: not only must each individual track go under the microscope – but can also he preserve the sense of unity and coherence over the whole set? Yes, it turns out.

Simpson himself is on piano, and he would be the first to acknowledge the contributions of his band: Tori Freestone and James Allsop on saxophones, Dave Whitford on bass and Will Glaser on drums. After performing this set together live, they recorded these album versions in one afternoon. As a result, they replace the original’s introverted hesitancy with a sense of excitement and drive: Yorke’s cut-up, repetitive lyrics from the original, that seemed to rein the ‘Kid A’ songs in, hold them back somehow – are, of course, now gone, and the tracks gain a renewed sense of purpose and forward motion.

This doesn’t mean any of the sensitivity is lost: far from it. ‘Treefingers’ is a virtually ambient instrumental on the original, a kind of looped chord sample that periodically renews itself. Simpson has percussion – rumbling toms and echoing cymbals – build the ambient ‘wash’, as delicately sustained piano dissolves into runs and trills before re-charging with a new chord, calling to mind the ‘release valve’ feel of the Radiohead version. Likewise the closing tune, ‘Motion Picture Soundtrack’, is barely there on ‘Kid A’, smothered in effects: Simpson exposes the beautiful melody using piano and saxophone, but then offsets it with a surround of percussion and second sax, honouring the original’s impulse to hide.

But if the aim of jazz is to surprise the listener, this group are on top of the brief. Anyone familiar with the title track of ‘Kid A’, its coiled riff perhaps the closest a song can sound to someone curling up into the foetal position, will be thrilled at how the band take its bare bones off in myriad different directions but preserve its stop-start restlessness and closing ‘mash-up’ of elements.

On the other hand, ‘The National Anthem’ – the Radiohead album’s most explicit nod to jazz – is skilfully harnessed into something more controlled and incisive. The insistent bassline is present and correct, but otherwise the track is turned inside out. The frontline horns providing the rhythms and, in a bravura individual performance, Simpson’s piano not only captures the throwaway vocal melody but leads the way in creating, solo, the sonic mayhem generated by an entire jazz group in the original. (Fortunately, everyone joins him by the end, so we’re not cheated of the track’s chaotic climax.)

For those tracks where ‘Kid A’ is at its most ‘song-like’, the ensemble waste no time in getting under the bonnet and re-tooling them in their own image. ‘Optimistic’ lives up to its title as the band take flight over a kind of demented samba-on-speed rhythm. ‘Idioteque’ hits a punch-the-air moment at around two-and-a-half minutes where the duelling saxophones are suddenly de-railed by the piano and bass imitating the keening vocal line (perhaps this is also one of Simpson’s favourite points, as the sung lyric here is “everything all of the time”).‘How to Disappear Completely’ is perhaps the most direct ‘cover’ here, using sax and piano to give us a loyal take on the original’s voice and guitar. But the restraint allows Freestone – here providing pared-down ‘swoon’ on violin – and Glaser to truly shine. (Listen out, too, for Glaser’s extraordinarily measured opening solo on ‘Morning Bell’.) It demonstrates how Simpson’s band mesh so well together that they can use their instruments to create a sense of ‘noise’ amid the melodies (a role played by glitchy samples and electronics on ‘Kid A’ itself).

To end at the beginning, one track that I think gloriously sums up the whole enterprise is ‘Everything in its Right Place’. It’s a modest start, over a minute shorter than the Radiohead version. It treats the original with respect, the haunting hook and progression in place, but in no time at all every band member has made their mark on it, Simpson finding endless melodic avenues around the pattern, Freestone and Allsop working in telepathic tandem to briefly bend and shape the tune in Simpson’s wake, while Whitford and Glaser awaken the beat into buoyant, unpredictable life.

Like the whole album, it brings the claustrophobic, insular world out into the light. It takes something electronic, trapped in its own machinery, and lets it breathe acoustically, on real instruments. It takes music borne of difficulty, intensity and uncertainty, and replays it with spontaneous, natural exuberance.

*

Rick Simpson’s ‘Everything All of the Time: Kid A Revisited’ is available to order now on vinyl, CD and download from the artist’s Bandcamp page: https://rick-simpson.bandcamp.com/album/everything-all-of-the-time-kid-a-revisited

Sunday, 18 October 2020

Concrete jungle: 'Among the Trees', Hayward Gallery, Southbank Centre

As you may know, I am one of the writing team on Frances Wilson's ArtMuseLondon website, where this article first appeared. For a handsome range of reviews and thought pieces covering all genres of art and music, please pay the site a visit here.

*

At a time when the outside world desperately needs to recognise the importance of the arts, it’s fitting to see an entire exhibition of art on a mission to engage directly with the outside world.

‘Among the Trees’ includes pieces from 37 artists (based worldwide), working in a range of media: as we wander through the gallery’s twisty one-way path, we’re treated to painting, drawing, photography, video installation and sculpture. One or more trees feature in every work – no surprise there: as the gallery guide tells us, these are “artworks that ask us to think about trees and forests in different ways”.

How do we think about trees and forests? And why are they such constant features in our art, our consciousness even? I would guess that it’s something more than their innate beauty – in an increasingly volatile natural world, a love of trees is one of the ways we grasp at permanence. (Even mountains – those other, literal rocks of our imagination – no longer seem as immutable, immortal, as climate change attacks their snowcaps and glaciers.) No-one is claiming that trees are immune to these ravages – far from it – but they outlive and survive us, while showing us frequent revival, regeneration and resilience.

This symbolic quality, I feel, is what makes this very much a ‘Hayward’ exhibition – whereas you might expect a show devoted to trees to appear at a museum or botanical garden. The trees provide the ongoing motif around which we weave our attitudes, behaviour, history and politics. Inevitably, the impact of our resulting actions often turns them into our real-world victims, even accomplices. We’re in the (wooden) frame here – this isn’t ‘about’ the trees, after all, but us ‘among’ them.

I found Sally Mann’s photography almost unbearably evocative: using only technology that would have been available at the time, she has created images of Deep South locations that don’t flinch from the macabre associations of the trees they feature. While the blurred elements might speak to our wish that these impulses belong in the past, the tree itself – potentially weaponised – is in sharp, unforgiving focus. Nearby, the message is underlined by a photograph of a ‘lynching tree’, taken by the director Steve McQueen, while he was filming ’12 Years a Slave’ in Louisiana.

The starkness of this picture highlights the way the exhibition sometimes sits between art and reportage, some of the artists using their particular modes of expression to make us ‘re-see’ what is right there in front of us. Jeff Wall provides a signature massive photograph called ‘Daybreak’: beneath an empty sky occupying more or less the top half of the image, Bedouin olive pickers sleep next to the olive grove where they work. At first glance, Wall’s composition gives us descending lines of shapes hugging the ground: the low canopy of the trees, the sleeping figures, the rocks and stones. But on the horizon, the flat roof of a huge Israeli prison is visible: Wall tells us he was interested in the contrast between the Bedouin, free to sleep in the open air, and the inmates confined to their cells. The trees seem to provide a barrier between the workers and the prison: it is easy to infer that, to these people, the grove is nourishment, protection, a lifeline. Yto Barrada’s acutely observant photography uses the ability of trees to persist in growing under difficult conditions to highlight the surrounding scenes of urban monotony or decay.

By contrast, Johanna Calle creates a wholly unnatural image, with ‘Perímetros (Nogal Andino)’: a silhouette of an Andean walnut tree. Closer inspection reveals that the dark expanse is in fact a typed transcript. The wording comes from Colombia’s Law of Land Restitution (2011); the paper from an antique land register, and the tree itself symbolises land ownership. As the gallery notes say, the piece fits into the context of Calle’s other work, which “questions the power and authority of the written word over oral traditions” – here that is, I understand, the fact that the complex texts of modern lawmaking can only attempt to do what planting trees once achieved. For me, it’s also a work of absences: the innovative medium means we do not get to see Colombia, nor those whose land was stolen. Its aesthetic of stylised typography means the tree is only suggested, not actually there: a coolly eloquent expression of displacement. Fittingly, the exhibition also includes work by one of the displaced, Abel Rodriguez, who relies on his memory to paint the home he left behind.

Some of the exhibition’s most powerful work found the artists using the tree as a kind of organic mirror, the better to examine themselves and their practices. Kirsten Everberg, heavily influenced by film locations, paints a birch grove, ‘lit’ in the manner of Tarkovsky’s ‘Ivan’s Childhood’. Zoe Leonard’s photographs evoke the strain against creative boundaries through images of trees pushing through fences or outgrowing confined spaces. George Shaw’s charcoal drawing of a fallen tree – a starker, monochrome contrast to his usual paintings apparently inspired by his father’s death – is inescapably poignant. We see not just the collapse of the trunk, but the exposed, unearthed roots. Two photographers – Rodney Graham and Robert Smithson – give us ‘upside-down’ trees, both prompting us to look at the subjects almost as abstract patterns (Graham) or systems (Smithson) without our pre-set ‘tree-love’ doing half the work for us.

There are spectacular pieces from contributors tackling environmental issues head on. Two brilliant, large-scale video installations challenge our powers of observation. Jennifer Steinkamp’s ‘Blind Eye, 1’ is a digitally-manipulated animation showing an ‘impossible’ forest (we are in the thick of it, with no floor or canopy to orientate us) rattle through all four seasons in three minutes. It’s a bravura contrast with Eija-Liisa Ahtila’s multi-screen film of a spruce. The images are turned 90 degrees, so that we see the tree sideways – bringing home the notion that we see the tops of trees so rarely compared to the bases: what other details do we routinely miss? On the subject of spruces, there is Rachel Sussman’s photograph of a 9,500-year-old specimen that has been quite happy close to the ground for all that time, until the warming climate forced a late growth spurt over the last 50 years. An extraordinary ‘trompe l’oeil’ sculpture by Kazuo Kadonaga re-assembles a cedar tree from hundreds of thin paper sheets it was used to create.

I can’t mention everyone, of course, but I think the real power of the exhibition lies in its collective, cumulative effect. Putting down metaphorical roots, the trees do provide a consistent, conceptual still point that can withstand the storm of messages and statements around it. It’s impossible to take in the show without your mind filling with contradiction and conflict. For example, the irony cannot be lost on the artists that in most cases, trees have been sacrificed to bring their work into existence.

And, as I so often find with the Hayward, the gallery almost always seems to become one of its own exhibits. Part of the brutalist monolith of London’s Southbank Centre, the space’s unforgiving, slab-concrete shell means that the hang itself is a kind of surreal triumph, daring the natural world to gain the upper hand. Please go if you get the chance.

*

‘Among the Trees’ is now running to 31 October.

While current restrictions are in place, you must book a timed ticket in advance, at https://www.southbankcentre.co.uk/whats-on/art-exhibitions/among-trees?eventId=855751

Photos by me.

Saturday, 3 October 2020

Across time and space: Carolyn Sampson & Matthew Wadsworth at Wigmore Hall

Even if there had been no lockdown, and no live music drought to go with it, I think I would have been excited about this concert to borderline-unmanageable levels.

Saturday, 19 September 2020

Promentum!

- I’ve asked the question before: why can we not have a regular classical music TV show? The answers ‘it’ll cost money / no-one will watch it’ are inadequate, because the BBC believe (rightly) there is a home audience for the Proms for the entire season, including a magazine show, which disappears when the Proms end. But the audience – now Prom-less – are still there! The programme could feature sessions (like a classical ‘Later’) or profiles, look at new releases, and so on.

- It would be great to see any performers (who are able to) explore outlets for their music that don’t necessarily rely on record companies and certainly not on streaming. Bandcamp is a key contender here – if you are a solo instrumentalist, art song duo, small band – whatever works – and you can record your music to a level you’re comfortable with, please consider or investigate releasing it yourself as a download. (Lisette Oropesa is a high-profile example.)

- I realise that for some, this might mean certain compromises – available technology, sound quality, performance acoustic – but, while I love gorgeously-recorded CDs as much as anyone, I also think perfection is a bit of a cult. In rock, folk or jazz, people become accustomed to – and happily seek out – something a little more rough and ready (the popularity of bands releasing demos, alternate takes and live albums testifies to this). It’s no coincidence that fans have been overjoyed to hear Angela Hewitt or Igor Levit simply film their hands at their home piano, or watch multiple-view choirs singing ‘together’ but remotely. It’s the music we need to hear, with the added bonus of taking us closer to our favourite artists’ processes. It doesn’t ‘replace’ live performance (as lockdown has shown us), but it can complement it, once lockdown is a memory. The idea that classical music needs to be ‘pristine’ is something imposed upon it, not innate.

Monday, 7 September 2020

10 x 10

Sunday, 23 August 2020

Window to the inner world: Heather Leigh, 'Glory Days'

As you may know, I am one of the writing team on Frances Wilson's ArtMuseLondon website, where this article first appeared. For a handsome range of reviews and thought pieces covering all genres of art and music, please pay the site a visit here.

*

Heather Leigh’s previous release, ‘Throne’, was one of my favourite albums of 2018. Picking up the record unawares, you might expect country rock – Leigh sings, and her chief instrument is pedal steel guitar – but that would be a mistake. On first listen, you might wonder just what it is you’ve let yourself in for. Then, a track or two later, you can’t fathom how you were ever without it.

Leigh’s work often presents the thrill of opposites, not least in the way she somehow belongs firmly in the avant-garde, yet at the same time produces such inviting, accessible music. She has other musical ‘lives’ – for example, her fearless improvisation duo with veteran saxophone wielder Peter Brötzmann – that perhaps explain the discipline she must need to assemble her intimate, intricate solo records.

‘Throne’ is an astonishing experience – a suite of music designed to be devoured whole (live, Leigh performed it in order, without pause). Building a wall of sound with pedal steel and effects kit, the backing ranges from luxurious to lacerating. Holding it all together is Leigh’s voice; blessed with character and range, she draws you in, close-miked, the intimate lyrics both confessional and confrontational, the flow of words somehow containing the music’s turmoil.

‘Glory Days’ is Leigh’s contribution to the series. However, she has produced another masterpiece which transcends the unusual way it was made; far richer than a swift demo would allow, this is a rewarding and complete work, very much a natural successor to ‘Throne’ while in some respects, representing its opposite (that word again!).

If ‘Throne’ was ‘considered’, say, in the sense that it was made in a studio, and conveys a narrative feel, of stories being shared – ‘Glory Days’ is unfettered. It is an experimental work – with 13 tracks in around 30 minutes, it can work perfectly well – in fact, works best, in my view – as a suite or cycle of songs united by its central idea. Leigh buys into Boomkat’s brief, bringing whatever’s around her: synthesiser and cuatro feature alongside the pedal steel, resulting in a record suspended between analogue and digital, acoustic and electric.

That open window also symbolises our disrupted relationship with ‘outside’ during lockdown. For some it’s totally off-limits, with potentially far-reaching consequences. For others, it’s accessible, but changed, or reduced. Leigh’s music is reaching for the out of bounds – nature, travel, not to mention gigs, collaborations, work – and gathering the elements it can get hold of indoors. One of the most beautiful and affecting tracks features delicately-picked cuatro and Leigh’s wordless vocal – as if leaving words behind might strengthen the connection with the birds also singing, high in the mix. Only its ominous title, ‘Death Switch’, hints at the precarious natural balance and artificiality of the bond.

But the additional depth in ‘Glory Days’ involves looking inwards, too. The album has a classical, minimalist feel in places, in the sense that it takes particular ideas and works them through to a conclusion. ‘Phrases on the Mount’ describes itself, as Leigh tests gradually changing – and climbing – versions of the opening line, as if in search of the perfect result, a game of lyrical consequences. ‘Aretha’ is blink-and-you’ll-miss-it short, a mantra that pulls your focus in to concentrate on the tiny shifts in timbre, and timing, even the breaths Leigh takes merging with the ambient hum.

Paring some tracks down to a single line in this way amps up their incantatory feel, as if we are party to a more ritualistic type of creation, an insight into lockdown seclusion. So much of the music just yearns, whether it’s in the fabric of the keening instrumentals ‘Molly’ and ‘Island’, or the disco pulse of ‘Take Just a Little’. Some of the repetition hints at obsession, making significant changes – and they do come – utterly seismic: no spoilers, but key moments like this await in ‘All I Do is Lust’ and ‘In the View of Time’.

This unique, uncompromising record presents Leigh’s mind to you a little like a transistor radio. We’re turning the dial, stumbling across transmissions that are fully-formed, perfectly realised, complete. But they already existed before we arrived, and they are still there now.

*

I’ve written about ‘Throne’ as well as ‘Glory Days’ – partly because I am sure that if you hear one you will want the other. Both are available from Boomkat Records here at these links.

Saturday, 8 August 2020

Simple pleasures?

This post first appeared on Frances Wilson's excellent blog 'The Cross-Eyed Pianist'. For a variety of features that - alongside a special interest in all aspects of piano playing and listening - focus on wider classical music and cultural issues, please pay the site a visit here.

*

The discussion that will not die: elitism in classical music. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve taken part in it, both in conversation and, here and there, in writing. What keeps it grinding on, blocking the through-routes to open-hearted enjoyment and appreciation?

Don’t worry – I can hear your response: people like you keep writing pieces like this! Well, touché. But this time, there are two particular prompts. First of all, pianist/composer Ludovico Einaudi – a genuine phenomenon – has made the news through one of the examination boards adding his work to the syllabus. Einaudi appears to be an almost satanic figure to certain folk in the classical music sphere, inviting levels of dismissiveness and vitriol in line with his sales.

In parallel, we are living through a very specific, unusual period where artists and musicians are suddenly without income and, in many cases, are forced to consider the future viability of their planned projects, even careers. The ‘normal’ to come may not be the ‘normal’ we had before. With that in mind, isn’t it better to consider and examine – rather than dismiss – what could make more classical music more popular?

Of course, programmers and marketing departments have grappled with this conundrum since the year dot, and concerns about bringing in audiences persist, even in a pre- or post-covid scenario. There is no magic solution. We’ve seen venues try wildly different approaches: adding new or untried pieces to a bill featuring a dead-cert, bums-on-seats, absolute banger; staging concerts or musicals ‘off-season’ to help fund opera; performing short, sharp rush-hour sets to whet commuters’ appetites for more… and so on. The outbreak is driving even more innovation along these lines – English National Opera’s upcoming ‘drive-in opera’ performances at London’s Alexandra Palace, for example.

But it’s up to us – the audiences, the listeners, the teachers, the fans – to grapple with this, too. Our minds need to be as open and welcoming as the doors to our favourite venues. Our conversation, our social media accounts, can spread the word as efficiently as fliers and mailing lists.

Because love of music will always revolve around taste, ‘arguments’ against Einaudi don’t really stick.

- “Just because it’s successful doesn’t make it good.” No, but it doesn’t make it bad either (leaving aside the obvious problem of who decides whether something is ‘good’ or not). In the same way, a piece is not ‘good’ just because it’s obscure.

- “It’s so simple, anyone could do it.” But ‘anyone’ didn’t do it. Perhaps they didn’t have the ideas or techniques after all. Or if they had the ideas, they didn’t have the patience, staying power and determination to get it all down and produce it.

- “It’s just pandering to popular culture / taste.” Well, isn’t that what composers and musicians want to do? If you have an income away from music that allows you to be utterly fearless and experimental in your art, fine: but surely everyone else is striving for the balance between staying true to themselves creatively and putting food on the table.

It’s not really a case of “I’m right and you’re wrong”: there is no right and wrong. If I like Einaudi, why should I care what the ‘establishment’ says about him? On one level, I don’t care one iota.

But widening the picture, it matters to me more, because to dismiss something because it’s too popular, not complex enough – not ‘good’ enough – is a form of gatekeeping, however accidental or unwitting. Whatever surface ‘elitist’ practices in classical music we may eventually conquer – high ticket prices, impenetrable etiquette, imaginary dress codes – a refusal to engage with and even embrace what fires up a wider, casual listenership will always stop us reaching the maximum possible audience.

I always have to remind myself that the dividing line between classical and popular music was only drawn in recent history. To pare one specific cliché down to its essence: “Modern classical music – where are the tunes?” As unfounded as that remark is, it comes from somewhere, and can’t be ignored. Perhaps during the twentieth century, as consumers increasingly got their ‘quick fixes’ from red-hot jazz sides, 3-minute salvos of rock ‘n’ roll and instantly alluring soul numbers, classical music went somewhere else: innovative, exploratory and definitely, even defiantly, more niche. (Otherwise, why would we need the term ‘light classics’ – themselves under fire from time to time – if there wasn’t some serious ‘heaviness’ elsewhere?)

Isn’t it time to bring these worlds together again? Isn’t it already happening? I type this on a Sunday in July. Nicky Spence brought a superb online concert (part of Mary Bevan’s Music at the Tower series) to a close with ‘Nessun Dorma’ to the audience’s utter delight, and no wonder: it’s one of opera’s bona fide entries in the hit parade, thanks to Pavarotti. And the ‘Bitesize Proms’ series posted a performance by counter-tenor Iestyn Davies and lutenist Elizabeth Kenny of… ‘There is a Light that Never Goes Out’, by The Smiths. Other examples spring to mind: Sheku Kanneh-Mason taking Elgar into the Top 10 mainstream album charts; Anna Meredith making electronica albums alongside her classical commissions; Max Richter curating a multi-disc compilation for Rough Trade introducing modern composition to indie/underground record buyers…

Information overload, shorter attention spans, more urgent need to multi-task: our culture and society is not just continually changing, but compressing. Like it or not, more people respond to the immediate, the impactful. For example, as an artist-led listener, I favour the increasingly popular approach of programming discs as though they were ‘albums’ rather than recordings. I willingly accompany certain artists on their creative journeys: the perfectly natural behaviour of a fan, essentially.

As listeners, the more that we can do to bring some of the impact found in other genres into the classical music world, the better. There’s no need to dilute the music itself – but no need to rarify it, either. We need to communicate our enthusiasm and excitement about classical music without embarrassment or inhibition…. And to do that, you have to let people in: not shut them out.