Two very different evenings to report back on at the Royal Opera House recently. First, the main stage production of Handel's 'Agrippina', directed by Barrie Kosky - followed by Nigel Lowery's revival for Music Theatre Wales of Gerald Barry's first opera, 'The Intelligence Park', in the Linbury Studio Theatre (itself revived to impressive effect in the recent 'Open Up' refurbishments).

I still feel like I've seen relatively few Handel operas, and most of those in a concert environment, rather than fully staged. So when it comes to the formality of the aria/recitative structure - that kind of stop-start effect where the story races on in swiftly-delivered passages between glorious, emotionally-intense soliloquies that give the individual singers the chance to take flight - I associate that more readily with the drama that arises from the energy of the performers rather than necessarily the engine of the plot. (A good example might be the brilliant concert performance of 'Orlando' from about three years ago, given by the English Concert at the Barbican, where the musicians and soloists - including Iestyn Davies and Carolyn Sampson - gave the evening a relentlessly affecting drive.)

So, I'm always intrigued by what directors will do with this structure - how do you keep things moving when time stands still? And none more so than this time round, with this director. I know Kosky attracts controversy - I'd only previously seen his ROH production of 'The Nose' (which I found both enjoyable and barking mad), and I know his current staging of 'Carmen' has attracted mixed responses. But, as enfants go, he seems to be not so much terrible, as un peu insolent, perhaps. After seeing his take on 'Agrippina', I suspect he receives (and deserves) widespread respect and admiration because he can bring a radical and arresting interpretation to a 'traditional' work without resorting to mere shock tactics or 'concepts' for their own sake: if anything, I felt his treatment made the work come alive for me in ways that perhaps it might not have done in other hands - who knows?

In 'Agrippina', there's a significant amount of plot to get through. After hearing that her husband, the Emperor Claudio, has died at sea, Agrippina wastes no time in engineering her son Nerone's claim to the throne. To this end, she manipulates Pallante and Narciso (court advisers who are both smitten with her) to agitate on Nerone's behalf. However, Claudio is in fact alive, and has promised his title in gratitude to his rescuer, the loyal Ottone. Ottone, in turn, is in love with Poppea - but then Claudio and Nerone are infatuated with her as well. To bring the succession back to her son, Agrippina begins to manipulate the emotional and political weaknesses of the other characters - and even when, at times, they occasionally seem to outmanoeuvre her (Poppea, in particular), she ups her game accordingly, until mission accomplished. (With, astonishingly, everyone else alive - for now - and in reasonably good shape.)

(Lucy Crowe as Poppea - 'Agrippina' production photos are by Bill Cooper, from the ROH website)

Deceit and mischief are in the fabric of the opera, so while this is my first 'Agrippina', it's hard to imagine any production playing it as totally serious or po-faced. But Kosky is careful not to over-egg the pudding. The monochrome set looks, if anything, austere: a box of connecting rooms and stairs, either open to the exterior or visible/concealed by blinds - it's simple at first to look at and take in. But that belies the complexity and skill behind how it moves and rotates to create certain perspectives and reveal only what we need to see at any given time. And for the most part, the costumes are low-key, too - but telling. Sober suits for the gents, apart from sulky youth Nerone, who we first see in drab grey jeans and hoodie. Any flamboyance is linked with power - when Nerone initially thinks the throne is his, he turns up in a kind of PiL-era John Lydon gaudy suit for the coronation... and - as my friend Jamie sharply observed to me afterwards - as Poppea begins to steal a march on Agrippina, her outfits become more and more glamorous, as Agrippina's are increasingly pared down.

I think Kosky must be a great director of - and have great trust in - his actor-singers, as the comedy and personality of the piece belongs to them. At the start, the characters must play their cards close to their chest - Pallante and Narciso, who in the opera's opening moments are still nursing secret passions for Agrippina, are bundles of nervous tension, in constant movement. The tone of the piece is, I would say, knowing: the characters use their asides and soliloquies to 'break the fourth wall' conspiratorially, but the cast mostly pull back from any mugging or descent into lunacy, maintaining instead a kind of mockumentary/satirical feel.

(The cast, 'Agrippina')

There is one set piece which nods overtly to farce - when Poppea contrives to have Ottone, Claudio and Nerone visit her simultaneously, then hide them all from each other. However, chaos does not ensue - in fact, Poppea breezes through the scene, operating the men like puppets with the clockwork confidence of the old-school 'Mission: Impossible' team. Even the opening-closing doors routine was despatched with apparent nonchalance, as several characters in the room-boxes were seemingly flattened, in one movement, only to reappear. Overall, the impression of sophistication far outweighed that of silliness.

Another aspect I felt made the opera feel very immediate and, arguably as a result, current was its groove. The Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment were in their element, and conductor Maxim Emelyanychev - directing from the keyboard - pushed them on at a comedy-thriller clip. I was in the Upper Slips - for the uninitiated, these are cheap seats very high up at the sides, so the deal is: you can't see the quarter or so of the stage nearest to you - but you are more or less right above the orchestra. Restricted view, then, but amazing sound. Looking down at the pit, then, I could have sworn at times that Emelyanychev had turned into Animal from the Muppets, a blurry form consisting solely of hair and arms. Theorbo player David Miller definitely appeared to be riffing at several points.

Because the music really swung, it's perhaps understandable that the rhythms found their way into the movements of the characters, with a gentle sway building to a passionate embrace, and - in one of the evening's stand-out sequences, a jubilant Poppea delivering an aria while throwing proper flamenco shapes between lines to express her exhilaration.

As Poppea, Lucy Crowe was charismatic and captivating. She has a graceful, yet dynamic onstage presence - in short, a brilliant mover (as anyone who saw her in the ROH production of 'Mitridate' or the more recent 'Cunning Little Vixen' at the Barbican can testify). Vocally, the entire cast hooked me in: in particular, as well as LC, Iestyn Davies sang with his special combination of sensitivity and steel as the brave but often understandably nonplussed Ottone; bass Gianluca Buratto lent Claudio the right mix of tomfoolery and threat; Franco Fagioli was unafraid to give Nerone a slightly abrasive edge that matched the character's sullen volatility.

Orbiting them all was the magnificent Joyce DiDonato with an appropriately commanding performance in the title role. She's just full of wondrous sounds and deeds. Agrippina is so mired in schemes that she almost needs to present multiple personalities at the drop of a hat, and JD had all of this in the singing as well as the actions: cooing and sighing when ensnaring a would-be lover, to purposeful and commanding when taking control (at one point, playing to the crowd through a mic).

(Joyce DiDonato as Agrippina)

It was one of those virtuosic displays where I could 'feel' her moving through timbres, moods, approaches while never sounding like anyone other than herself. An astonishingly beautiful sound, but totally wedded to a complex characterisation. All sides of the same voice.

That said, in Kosky's powerful and moving interpretation of the opera's close, Agrippina has achieved all she set out to achieve, so falls silent. JD also moves brilliantly here, slowly withdrawing into what looks like the smallest chamber in the set, and sits quietly, her expression almost unreadable as the blinds draw in front of her. This could perhaps foreshadow her real-life fate, eventually falling victim to the absolute power she helped her son attain. But I also felt that to see her fade vocally as well as visually drew a melancholy line under her 'my work here is done' triumph. (It reminded me a bit of a reverse version of the way 'Billy Budd' closes: the entire orchestra drops away, leaving Vere to make his final remarks unsupported, truly alone in the universe.)

*

Onto ‘The Intelligence Park’ a couple of nights later. Quite a contrast. I’d come across Gerald Barry’s work once before at a Barbican concert of his latest opera, ‘Alice’s Adventures Under Ground’ (coming soon to the ROH in a full staging). It was fun, fast, at times seeming like actual bedlam, bordering on collapse. And what do you know, back in 1990, he was conjuring up something equally frenetic for his first foray into the genre.

To be clear from the outset: I enjoyed this, and got a lot out of it. But it’s not for everyone. We lost some folk at the interval (by which I mean they left - the opera didn't actually kill them). It would be very easy to point at a lot of the action and say, ‘Well - this is just crazy.’ It is certainly breakneck and largely unhinged. But for accuracy, it’s something more than mad: madcap, I would say, and at times maddening.

There is a plot in there. The 1750s: The composer Paradies is struggling to write an opera, featuring a pair of lovers, Daub and Wattle. At the same time, his personal life is a tad complex: he’s about to marry into a wealthy family, but instead both he and his fiancée fall for her castrato singing teacher. She elopes with the singer - so, as fact and fiction blur in Paradies’ mind - Daub and Wattle come to life, merging identities with the couple until some kind of equilibrium can be restored. (I think, though I can't be sure, that the 'Intelligence Park' of the title might refer to how the characters and events of the opera 'play out' in Paradies' head.)

However, the language in Vincent Deane’s libretto is wilfully flamboyant and obscure (I understand he’s an authority on Joyce’s ‘Finnegans Wake’, which would go some way towards explaining a love of language and verbal sounds for their own sake - not to mention a resistance to plain English). Barry’s score seems to place almost impossible demands on the singers: sky-high passages for everyone, whatever their register; huge interval leaps; nightmarishly fast sections that stop and start unexpectedly, sometimes mid-word... and of course, the orchestra are manically keeping pace with all this.

(The cast - production photos of 'The Intelligence Park' are by Clive Barda, from the ROH website)

I was trying to work out the reason for it all. Certainly in this work, the themes include mental instability and creative block, so for the score to sound like an opera falling part would fit. And maybe these features of his style remain because of his attraction to zanily surreal subject matter (Wilde as well as Carroll).

While it can sound all over the place, it is not a mess. In fact, the further on we get in the opera - as events begin to coalesce - there are moments of slower-paced calm and harmony, throwing the mayhem that precedes it into relief. There clearly is a grand plan. I wonder if it's primarily meant as 'extreme opera', and you either throw yourself into it, or you don't. For example, every genre has its outer reaches: not all metal fans want to push it as far as, say, grindcore (bands like Napalm Death and Nasum - very heavy, VERY fast); not all jazz fans head straight for the totally free, atonal stuff. But some do, wanting to test the music and test themselves. If you have an appetite for that, 'The Intelligence Park' might be the sort of opera you're looking for.

As an extreme music lover, I think that's the main reason I had a good time. And the performers were equal to the work's demands: Jessica Cottis conducting London Sinfonietta - and a company of soloists who at times seemed almost superhuman in their valiant attempts to bend their voices around Barry and Deane's traps and obstacles. (Special mentions for Adrian Dwyer's arch companion D'Esperaudieu - at times the still point of the opera and our one-man chorus - and Rhian Lois and Patrick Terry as the lovers, wringing emotion out of warp speed lines.)

(Adrian Dwyer as D'Esperaudieu)

The staging itself was garish and the production hyperactive, as though it was felt necessary to match the intensity of the words and music. As an assault on the senses, this was right on the money, and it had a powerful impact. Deep down, though, for wholly different reasons, I wondered if it would've benefited from a touch of the restraint shown in the production of 'Agrippina' - whether dialling it down just slightly would have made it easier to handle and process the aural attack.

But I can hardly complain. Seeing these productions just two nights apart was as handsome a reminder as any of the sheer variety and richness available in the one artform.

Monday, 30 September 2019

Saturday, 21 September 2019

Show gardens

The other day I had one of those great experiences where something I was expecting to find enjoyable, relaxing, perfectly pleasant... turned out to be mindbendingly brilliant and inspiring. Step forward, London's Garden Museum, nestling snugly against the shoulder of Lambeth Palace, on the south bank of the river Thames.

Very pleasant walk along said bank to get there, too. Although the arachnophobe in me rather felt like the upturned-hulls installation in this forecourt was all too reminiscent of a beastie emerging from a plughole...

I confess that to me, 'garden' is mainly a noun, not a verb. I am not green-fingered in the slightest - but have always been utterly content to wander through and photograph public gardens as an ardent, if passive, admirer.

For all that, the Garden Museum had not really leapt out at me as a place to visit, and even this time we were there for a slightly left-field reason. Mrs Specs has a great interest in vintage children's books, so has been watching the re-emergence of Ladybird Books - both as a retro touchstone and a kind of re-vamped satirical vehicle for adult readers - with interest. The Garden Museum has mounted an exhibition of original watercolours from the beautifully-illustrated garden and nature books Ladybird used to publish - so I went almost as a +1, out of curiosity, to check it out.

That particular exhibition was small, but lovely - richly nostalgic. But I hadn't prepared myself for the sheer joy of just hanging out at the Garden Museum itself. As you can read on the museum's website, the building was an abandoned church, St Mary-at-Lambeth, which was going to be demolished until rescued by the museum founders, Rosemary and John Nicholson, in 1977. The link is that pioneering British plant-hunter, John Tradescant, was buried here.

Given the kind of ghost stories I like to read, I was conjuring up all kinds of 'Pet-Semetary-but-with-horticulture' visions of undead, and possibly vengeful, ancient gardeners rising from the dead to terrify tourists with trowels. But, surprisingly, no. In fact, it now feels like something of an architectural triumph, with an airy modern interior tracking the exterior shape of the church in serene harmony. (I also had no idea it was also a venue - for example, I found out that a couple of days after our visit, the new chamber opera by Robert Hugill and Joanna Wyld, 'The Gardeners', was given there, and I was deeply disappointed not to be able to go. But you can really imagine it in the space, as shown below, can't you?)

Inevitably, you can find a bit of the sinister in every museum (please note cat content - if this could go viral accordingly, that'd be lovely - thank you!) ...

But what really overwhelmed me - aside from the general interest and unusual aspect of the exhibits - were the unexpected 'indoor viewpoints' - by which I mean that I rarely felt I was 'just looking' at something. Almost every item or display brought with it a burst of light or architectural feature to enrich one's overall impression: I hope these shots at least give a glimmer of what I'm talking about.

Note that the second picture in that set of four was taken from literally inside a shed. See documentary footage below of Mrs Specs in the very same shed.

Perhaps it's no shock to reveal that one part of the museum that really fired me up was the section on garden design. These photos won't do justice to the immediacy of these, but hopefully they'll encourage you to investigate - I was particularly taken with this first one, for the Eden Project, where the landscape artist , Dominic Cole, embellished the architect's plan:

And the icing on the cake is unquestionably the view from the top of the Tower - we had a cloudy day so some of the pictures were a tad apocalyptic, but maybe that's appropriate for OUR TIMES.

I can't recommend the Garden Museum highly enough - please pay them a visit when you're next in the capital - or online, here.

A less apocalyptic cheerio from she and me:

...and an artificially speedy river boat.

Saturday, 14 September 2019

Crossing channels: Kevin Daniel Cahill's 'Future Relics'

This post first appeared on Frances Wilson's excellent blog 'The Cross-Eyed Pianist'. For a variety of features that - alongside a special interest in all aspects of piano playing and listening - focus on wider classical music and cultural issues, please pay the site a visit here.

*

What an exhilarating record this is. ‘Future Relics’ is the debut album from guitarist Kevin Daniel Cahill, and I think one of the reasons I love it so much is that it feels like it was made not only by a superb musician, but a great listener. As a result, it’s a great listen.

Reading a description of ‘Future Relics’ might initially make you think it’s more like two mini-albums or EPs gathered into one, as Cahill has assembled two very different ‘groups’ of pieces. One set is a series of classical commissions from composers he asked to write for the album, while theremaining tracks, written by Cahill himself, are rock instrumentals.

There’s certainly an intriguing legacy of ‘split personality’ albums in the rock world, where side one might have had the hits but side two was a playground. You might think of the ‘Abbey Road’ medley, or Berlin-era Bowie’s instrumentals on ‘Low’ and ‘Heroes’ – or even Kate Bush’s piece of audio-theatre, ‘The Ninth Wave’, taking up half of ‘Hounds of Love’. Others among you might come at this entirely differently, perhaps after a listen to fellow classical guitarist Sean Shibe’s recent ‘soft / LOUD’ album, half acoustic/ancient, half electric/modern.

But having identified these two separate sides of himself and his art, Cahill goes one step further and mixes them all up. Dovetailing the different styles of track in this way might seem, to coin a phrase, like a small step. But for the listener, it really is a series of giant leaps, with huge dynamic shifts from speaker-busting riffs and percussion to sparse, delicate picking. (The album is of course available digitally – so you can play any individual tracks you like, in any order you want. But as a measure of how important the sequencing is, I was interested to find that the only physical release of ‘Future Relics’ will be on cassette: the hardest format to ‘shuffle’…) So how and why does it work?

The album perhaps gestures most strongly towards the avant-garde with the commissioned tracks. Featuring Cahill solo, they are often steady and measured, almost at times with an improvisational, ‘working-things-out’ feel. The pieces are not in the least predictable, drawing all kinds of different timbres and harmonics from the guitarist. The combination of careful beauty and occasional savagery make you feel that whatever your accustomed style of player – from Xuefei Yang to Derek Bailey – something will resonate with you here. My personal favourite of these is Ninfea Crutwell-Reade’s ‘Wallflower’ – slightly more fleet-footed, it starts with what sounds like a chiming lead line, only to use it to create cyclic rhythm, while a ‘true’ lead comes in simultaneously, keening, adding a ‘sheet’ of sound almost to ‘”Heroes”’ effect. Haunting yet joyful – a wonderful work.

Despite their immense heaviness at times, the rock numbers also deploy resources with real care and precision. Cahill provides most of the tracks’ heft, with hooks, riffs or drones as required, and gives generous periods in the spotlight to acrack team of fellow musicians. For example, violinist Abigail Young provides the exotic, hypnotic swirl central to ‘We’ve Taken Aqaba!’. On both this track and the fearsome ‘For Deckard’, Graham Costello plays the drums more or less as a lead instrument, driving the piece forward while constantly shifting patterns and rhythms and increasing the intensity. Cahill again finds melody in the metallic, fashioning distorted chords into tunes.

But it isn’t all strum und drang, with quieter electric pieces punctuating the album. The gorgeous, but propulsive shimmer of ‘They speak in never ending light / Resting place, God’s Acre (For Andra)’ manages to look both ways – towards the cyclic sound of ‘Wallflower’ and the more driven, agitated thrust of ‘For Deckard’. The expansive sound occasionally made me think of the peculiarly Scottish feel of ‘Big Music’ (as coined by the Waterboys’ Mike Scott) in whatever form that may take for you: whether it’s split-second echoes of Local Heroics, or sudden bursts of barely-controlled Mogwai-style power.

Of course, it’s Cahill himself who is the unifying force across the whole record. He has shaped it – clearly he absorbs and goes on to write and play all the different styles of guitar music he loves. At the start of the album, we hear muffled voices and noise, as if the overall experience is going to represent a kind of ‘KDC FM’, with us moving between the various stations.

There’s also a strong sense that Cahill is channelling all these sources of inspiration into one style: his own. For all the reference points I’ve mentioned, throughout the album, he sounds like no-one other than himself – graceful, yet rhythmically robust on both the self-penned and commissioned material. I think the production is also a key element: ‘Future Relics’ is very concerned with the physicality and action of playing. We can hear the movement of hand and fingers against strings; the breathing; ambient hum and static – whatever’s going on, you feel like you’re in the room. This analogue touch will only be enhanced when played on a not-quite-silent cassette.

By representing his wide variety of musical passions, Cahill has made a bold record which will certainly introduce some listeners to styles of music they might not have been expecting. In doing so, however, he has in fact made an admirably coherent statement, demonstrating how one’s own work can successfully reflect many sides to the same person.

Rewarding; recommended.

*

What an exhilarating record this is. ‘Future Relics’ is the debut album from guitarist Kevin Daniel Cahill, and I think one of the reasons I love it so much is that it feels like it was made not only by a superb musician, but a great listener. As a result, it’s a great listen.

Reading a description of ‘Future Relics’ might initially make you think it’s more like two mini-albums or EPs gathered into one, as Cahill has assembled two very different ‘groups’ of pieces. One set is a series of classical commissions from composers he asked to write for the album, while theremaining tracks, written by Cahill himself, are rock instrumentals.

There’s certainly an intriguing legacy of ‘split personality’ albums in the rock world, where side one might have had the hits but side two was a playground. You might think of the ‘Abbey Road’ medley, or Berlin-era Bowie’s instrumentals on ‘Low’ and ‘Heroes’ – or even Kate Bush’s piece of audio-theatre, ‘The Ninth Wave’, taking up half of ‘Hounds of Love’. Others among you might come at this entirely differently, perhaps after a listen to fellow classical guitarist Sean Shibe’s recent ‘soft / LOUD’ album, half acoustic/ancient, half electric/modern.

But having identified these two separate sides of himself and his art, Cahill goes one step further and mixes them all up. Dovetailing the different styles of track in this way might seem, to coin a phrase, like a small step. But for the listener, it really is a series of giant leaps, with huge dynamic shifts from speaker-busting riffs and percussion to sparse, delicate picking. (The album is of course available digitally – so you can play any individual tracks you like, in any order you want. But as a measure of how important the sequencing is, I was interested to find that the only physical release of ‘Future Relics’ will be on cassette: the hardest format to ‘shuffle’…) So how and why does it work?

The album perhaps gestures most strongly towards the avant-garde with the commissioned tracks. Featuring Cahill solo, they are often steady and measured, almost at times with an improvisational, ‘working-things-out’ feel. The pieces are not in the least predictable, drawing all kinds of different timbres and harmonics from the guitarist. The combination of careful beauty and occasional savagery make you feel that whatever your accustomed style of player – from Xuefei Yang to Derek Bailey – something will resonate with you here. My personal favourite of these is Ninfea Crutwell-Reade’s ‘Wallflower’ – slightly more fleet-footed, it starts with what sounds like a chiming lead line, only to use it to create cyclic rhythm, while a ‘true’ lead comes in simultaneously, keening, adding a ‘sheet’ of sound almost to ‘”Heroes”’ effect. Haunting yet joyful – a wonderful work.

Despite their immense heaviness at times, the rock numbers also deploy resources with real care and precision. Cahill provides most of the tracks’ heft, with hooks, riffs or drones as required, and gives generous periods in the spotlight to acrack team of fellow musicians. For example, violinist Abigail Young provides the exotic, hypnotic swirl central to ‘We’ve Taken Aqaba!’. On both this track and the fearsome ‘For Deckard’, Graham Costello plays the drums more or less as a lead instrument, driving the piece forward while constantly shifting patterns and rhythms and increasing the intensity. Cahill again finds melody in the metallic, fashioning distorted chords into tunes.

But it isn’t all strum und drang, with quieter electric pieces punctuating the album. The gorgeous, but propulsive shimmer of ‘They speak in never ending light / Resting place, God’s Acre (For Andra)’ manages to look both ways – towards the cyclic sound of ‘Wallflower’ and the more driven, agitated thrust of ‘For Deckard’. The expansive sound occasionally made me think of the peculiarly Scottish feel of ‘Big Music’ (as coined by the Waterboys’ Mike Scott) in whatever form that may take for you: whether it’s split-second echoes of Local Heroics, or sudden bursts of barely-controlled Mogwai-style power.

Of course, it’s Cahill himself who is the unifying force across the whole record. He has shaped it – clearly he absorbs and goes on to write and play all the different styles of guitar music he loves. At the start of the album, we hear muffled voices and noise, as if the overall experience is going to represent a kind of ‘KDC FM’, with us moving between the various stations.

There’s also a strong sense that Cahill is channelling all these sources of inspiration into one style: his own. For all the reference points I’ve mentioned, throughout the album, he sounds like no-one other than himself – graceful, yet rhythmically robust on both the self-penned and commissioned material. I think the production is also a key element: ‘Future Relics’ is very concerned with the physicality and action of playing. We can hear the movement of hand and fingers against strings; the breathing; ambient hum and static – whatever’s going on, you feel like you’re in the room. This analogue touch will only be enhanced when played on a not-quite-silent cassette.

By representing his wide variety of musical passions, Cahill has made a bold record which will certainly introduce some listeners to styles of music they might not have been expecting. In doing so, however, he has in fact made an admirably coherent statement, demonstrating how one’s own work can successfully reflect many sides to the same person.

Rewarding; recommended.

Sunday, 1 September 2019

Doors of perception: Félix Vallotton at the Royal Academy

I'd been aware of this Swiss artist ever since viewing a few of his paintings on a visit to his native country some years ago. I was instantly taken with the work, although I never really put my finger on why. The best idea I think I could muster at the time was that there was a sense of eeriness that drew me in. It wasn't that something wasn't quite 'right' with them - on the contrary, I think many of the paintings are beautiful, with an instant appeal. I can only say that in some of the images, it felt like I wasn't looking at a purely 'normal' scene; I was seeing through distant, detached eyes.

So I was thrilled to see that the Royal Academy were mounting an entire Vallotton exhibition - and doubly intrigued to find they had subtitled it 'Painter of Disquiet'. Because there was no better word than 'disquiet' to finally nail the feeling I had on first seeing his pictures back in the day.

Apparently Vallotton regarded himself as something of an outsider, even within his own Parisian artistic circles (perhaps he always felt the new arrival). But you can draw lines from this innate 'apart-ness' into certain features of his art. For example, I was astonished by how many of his images feature doors and windows that give a slight imbalance to the composition, as though inanimate voyeurs of the scene taking place.

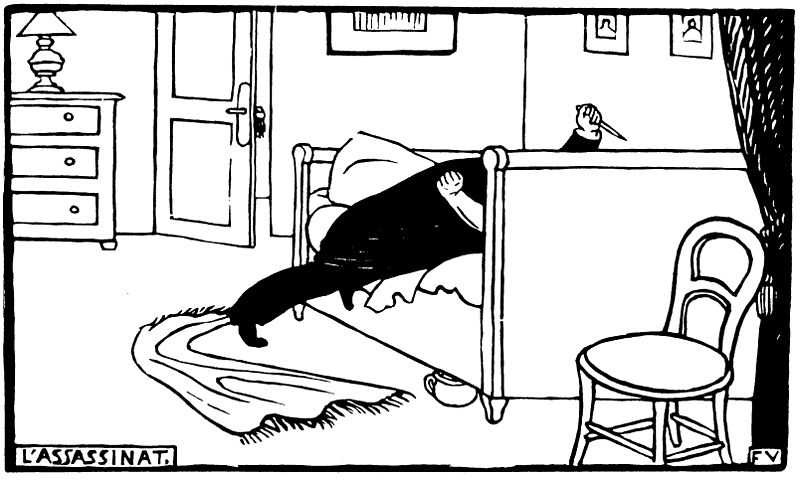

And this extends to his astonishing woodcuts (the exhibition makes the case for Vallotton as a print-maker extraordinaire - and I would agree - despite the artist eventually deciding that painting was his true calling).

As the above picture shows, Vallotton wasn't afraid of the dark - thematically as well as aesthetically. The killer is a black void in bright surroundings, only matched for shade by the drawn curtain.

Even when there is no door or window, Vallotton often seems to use darkness in this way to suggest a kind of ominous presence, or all-seeing-eye. The exhibition notes flag up the shadow which seems to follow the little girl chasing the ball. (And I wouldn't mind knowing what the two characters top left are doing there, too.)

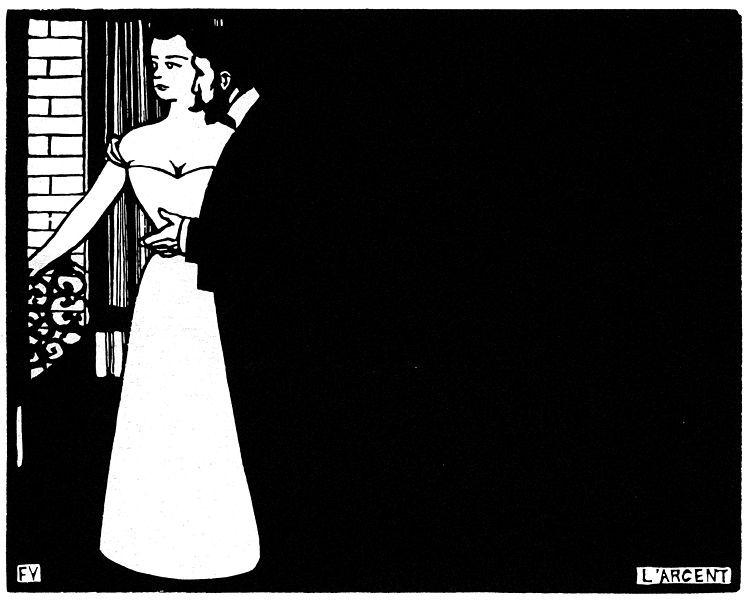

I think 'Money' is one of the most impressive woodcuts in the whole collection. The woman tries to stay engaged with the light (an off-centre window, of course), but the predatory male brings enveloping darkness with him, through whatever suggestion - or indecent proposal - he's making.

For all the sinister overtones, Vallotton's apparent detachment surely contributed to his talent for giving some of his woodcuts a satirical 'cartoon' life, which in some cases seems to flip over into untarnished, even generous affection. The musical instruments series is a masterclass in visual wit. And perhaps one of the most straightforwardly pleasing images in this vein is 'Laziness' - a gloriously busy and intricate display of patterns, calmed by the serene white expanse of the nude subject. She (along with her cushions) brings the relaxed curves to the hard-edged straight lines of the throw on the couch or bed. (Also worth noting that the picture includes a cat, which I include in the hope that this will now surely go viral on the internet.)

While I found his woodcuts arrestingly original, as a painter, Vallatton seemed initially a bit of a magpie to me/ It's interesting to imagine him picking up stylistic features - a Degas-reminiscent dancer here, a Hodler-shaped cloud there - as though one might pick up an accent.

...But the results always carry a slightly offbeat 'twist', whether it's the point of view, colour palette or choice of subject. One of the great achievements of the exhibition for me was that, whatever Vallotton turned his hand to, by placing his whole career together in this way, we can see the evidence of a single mind at work throughout. Even if corners of that mind remain elusive, unknowable.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)