Of course, some record labels have a very particular aesthetic that seems to elevate them - rightly or wrongly - above their roster of individual artists. Those of you sharing my vintage may well recall Manchester's Factory, which favoured the austere, industrial sleeve design of Peter Savile over band photos. Perhaps the most successful and fitting use of this kind of approach is ECM, where the clean, sparse, yet atmospheric and often abstract sleeves encapsulate the meticulous production values of the recorded sound. The label almost steps back, self-effacing, an anti-identity in complete service of the musicians.

But much as I admire this kind of approach, it can't win my love in the way that, say, Blue Note's unforgettable album covers can: Francis Wolff's majestic photography, married to bold typography that gives the sleeve a level of design class that a Saul Bass opening sequence would lend a film.

Or - looking through a different lens - the extraordinary sleeves Morrissey collated for The Smiths: together, a kind of second-hand, self-defining portrait archive drawn from movie stills and publicity shots that located the band's records in a very specific universe.

However, talking of very specific universes: on discovering and exploring classical music, I was if anything even more intrigued by the way a lot of the records - admittedly, more often than not shrunk to CD size nowadays - actually looked. To reel off the clichés: overwhelming quantities of decorous paintings, drawings of the relevant composers with forbiddingly serious countenance, and elder-statesmanlike portraits of conductors - presented with a kind of solid, furrowed intensity that could convince you Karajan had been carved out of Mount Rushmore.

It struck me that the visual presentation of classical recordings must have always presented a peculiar set of challenges. To begin with, there's the scholarly 'catalogue' aspect (no doubt feeding into the music's ongoing, regrettable dry/academic/elite image) of including all the necessary information in the title: composer, piece, conductor, soloists, orchestra, etc. Fine art must have been a very welcome option, not just in keeping with 'tradition'/'history', but also sidestepping any decision about exactly how many people to try and get onto the cover.

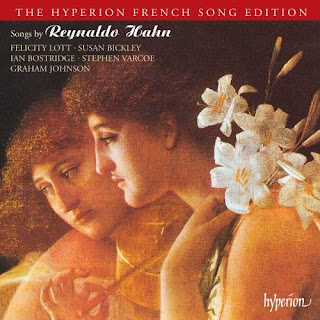

(The marvellous Hyperion record label has a house style of sorts - line up their CDs on your shelf and you'll see that the spine typeface is almost always the same - but it seems caught between these old and new styles of presentation: compare these art song titles, and you'll see quite a difference between the 'old school' Strauss and Hahn covers and the striking portraits of the Liszt and Brahms series.)

How do you get past the fact of so many releases called more or less exactly the same thing? - how many thousands of 'Beethoven: 5th Symphony's must there be? It's perhaps no wonder that the conductor in particular often becomes the 'brand' of a recording, and their noble visages still grace their latest projects: think of how Riccardo Chailly appears on the Gewundhausorchester Brahms and Beethoven cycles, or the current Elgar sequence from Staatskapelle Berlin under Daniel Barenboim, where the maestro appears almost preserved in an Old Master-ish sepia.

Entire books have been written and assembled about album sleeve design, and rightly so. All I have here is a blog post, but I mainly want to flag a few recent examples I've noticed in the classical genre where some of the conformities and constraints seem to have been more relaxed. I hope this becomes at least a tendency, even better a trend. Listeners like me who come to classical after rock, jazz, folk and so on are so often 'artist-led' and used to 'albums', rather than 'works'.

Sometimes it's as simple as owning something by naming it. I'm interested in how Rachel Barton Pine gives her records an extra title that 'overlays' the contents - and instantly announces the releases as albums - more personal projects, somehow, than 'mere' recordings. The DG label seems to be trying the same thing with the Liszt release from Daniil Trifonov. And the Andris Nelsons Shostakovich discs - which clearly nod to the 'austere conductor portrait' tradition - acquire an extra brand boost with the overarching title 'Under Stalin's Shadow' - something that will bind this series of CDs together to tell some kind of story alongside the music.

I find it very satisfying when the visual art seems to communicate something very specific about the performers. Florian Boesch and Malcolm Martineau are an ideal lieder team: in Schubert's songs where the voice and piano are so often equal partners, FB's willingness to almost 'step back' and allow his baritone to melt into MM's characterful playing makes for a near-perfect balance between them. So I wonder if it's coincidence that the art for their Schubert song-cycles on Onyx gives both men equal weight: two halves of the same enterprise. (I'd also love to know what prompted the 'slight' change of tack for the fourth CD of stand-alone lieder - certainly eye-catching! - although the fact that these are 'unconnected' songs in a variety of moods is well conveyed by the miniature repeats of the 'faces' motif in a range of colours.)

Some of my favourite singers and musicians are building bodies of work featuring intriguing and adventurous approaches to performance and programming - and the photography and design surrounding their music only underlines this. I don't see it as incidental that singers so often 'present' in this way - as, much like in the rock world, they are essentially in the 'frontman/woman' role.

Carolyn Sampson's recital albums with Joseph Middleton for BIS are strongly thematic (flowers, followed by the poetry of Verlaine) and the CD covers feature striking images of CS in line with the concept (surrounded by blooms, then beneath a shimmering 'clair de lune'). The forthcoming album of mad songs promises to have her appearing as the ill-fated Ophelia on the sleeve. But for their current release, where the duo team up with Iestyn Davies, the photo on the cover is a brilliantly bold, almost stark, double portrait: not only is it a great shot, but could you better capture the way the music on the CD itself marries 'old' and 'new' material and interpretations? ID exudes similar levels of cool on the sleeve of a recent Hyperion Bach disc, the font on the front of the sheet music echoing the record label's own distinctive logo, but both delightfully out of time with the rest of the composition.

This final selection, to me, seem to attain a kind of extremity of design - perhaps no surprise, given that they mostly belong to the work of Barbara Hannigan, renowned for her powerful and highly physical performances, and - I think it's clear - someone very much in control of curating her image. From the icy pallor of the 'let me tell you' song sequence (more Ophelia), through the candid nonchalance of the Satie recording with Reinbert de Leeuw - possibly the least diva-like cover shot you could imagine - right up to the stylish abandon adorning her new album: these all have the distinction of being shots it's impossible to imagine featuring anyone else. Likewise, my closing choice, the most recent CD from Anna Prohaska - another inventive recital programmer, here collecting 'Arias for Dido and Cleopatra' - explaining the astonishing cover portrait's arresting combination of tattoo and terror in the eyes.

I could have chosen so many more, but I think time and space (which just about covers everything) are against me. Maybe a follow-up post will conjure itself up in the future.

No comments:

Post a Comment